Log In

Remember meForgot password?

Forgot Password?

Pulp Fiction

Gather around, kids, and I'll tell you a tale of what it was like to see the movie that changed everything on its opening weekend — going in cold with little idea what it was about and no idea what I was in for.

It was the fall of 1994. I was deep into my own private post-college Gen X slacker wasteland, trying to figure out what to do with a never-quite-finished degree in English. I had spent a year wandering Europe, then another year writing a novel that nobody wanted. I took a job at a book store that went out of business shortly after I started, and then another at a record store that did the same.

If you're all right, then say something.

The internet wasn't much, and what it was wasn't pretty. There was no streaming, no YouTube, no Rotten Tomatoes. The closest you could get to a spoiler was digging deep in an AOL chat room. My small-town newspaper published at most three movie reviews per week — usually syndicated from Roger Ebert — and if more than three movies opened that weekend, you took your chances. I was a regular at my local indie arthouse cinema, but if Reservoir Dogs had played there, I must have missed it — which is all a long way around to saying that Pulp Fiction seemed to come out of nowhere.

We all know the story by now — or stories, I should say: Vincent and Jules and the briefcase; Butch and his gold watch; Honey Bunny and Pumpkin holding up the diner. In fact, we know these stories so well, and so many people have written so many words about this movie, that I'm surprised so many of you have requested that I break it down on this site.

Do you wanna continue this theological discussion in the car, or at the jailhouse with the cops?

Pulp Fiction was a blast to watch that first time — and the many times since. It was exhilarating. It was shocking. It was fun. Afterwards there was so much you wanted to talk about with your friends: Mia's overdose! The adrenaline shot! The hillbilly basement! The briefcase! The dialogue! Travolta's dance! I shot Marvin in the face!

And then there was this ongoing debate: Pulp Fiction was proof that you don't need three acts vs. counter-arguments that actually, yes, Pulp Fiction follows a three-act structure.

That argument didn't seem interesting or relevant to me at the time. I wasn't trying to write screenplays. If I had considered myself a writer, it would have been as a novelist. I related to the movie's non-linear and even circular end-at-the-beginning narrative (Finnegans Wake, anyone? Or Dhalgren?) that allows Vincent to live on in our minds even though we've already witnessed his brutal bathroom death. This calls to mind Tarantino’s later flirtations with alternate histories of World War 2 and Sharon Tate. What is the point of art after all, if not to allow the dead to live forever?

Say “what” again.

But while Pulp Fiction didn't inspire me to start writing screenplays (someday maybe I'll tell you about a little show called Buffy the Vampire Slayer) it did inspire a lot of other people, for better and worse. It kickstarted indie filmmakers in genres beyond just pulp crime — and its success went a long way toward giving a certain producer-who-shall-not-be-named the power to do all that he did.

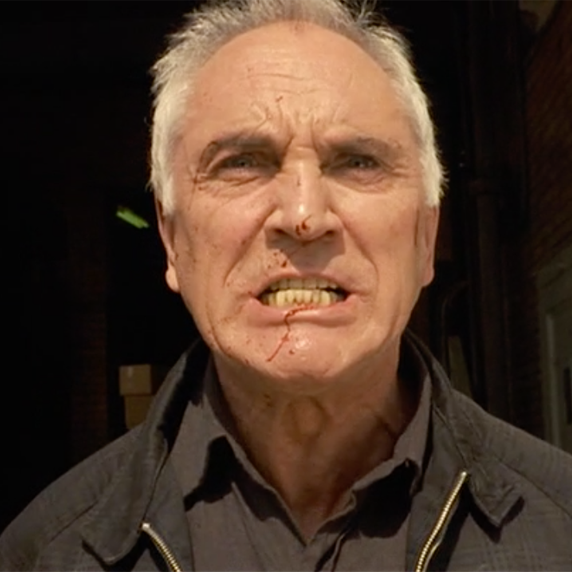

Medium Shot — Butch Coolidge

We FADE UP on BUTCH COOLIDGE, a white, 26-year-old prizefighter. Butch sits at a table wearing a red and blue high school athletic jacket. Talking to him OFF SCREEN is everybody's boss MARSELLUS WALLACE. The black man sounds like a cross between a gangster and a king.

Marsellus (O.S.)

I think you're gonna find — when all this shit is over and done — I think you're gonna find yourself one smilin' motherfucker. Thing is Butch, right now you got ability. But painful as it may be, ability don't last. Now that's a hard motherfuckin' fact of life, but it's a fact of life your ass is gonna hafta git realistic about. This business is filled to the brim with unrealistic motherfuckers who thought their ass aged like wine. Besides, even if you went all the way, what would you be? Feather-weight champion of the world. Who gives a shit? I doubt you can even get a credit card based on that.

A hand lays an envelope full of money on the table in front of Butch. Butch picks it up.

I think that what's more interesting and more instructive for writers than analyzing the structure of Pulp Fiction is analyzing the arc (or at least the beginnings) of Quentin Tarantino's career — and as a cautionary tale, I'll compare it to my own.

I'm here to help. If my help’s not appreciated then lotsa luck, gentlemen.

Quentin Tarantino made his first feature film (My Best Friend's Birthday) in 1987, and by his own account, in spite of his high expectations, it was terrible. It was unreleasable. I wrote my first novel in 1991, and it was terrible too. It was also unpublishable, at least by 1991's higher standards.

The difference is what happened in the next few years. Tarantino decided to consider his failure as his own private film school. He took what he learned from making that first film and applied it to writing, funding, and filming his Reservoir Dogs short (1991) and then Reservoir Dogs itself (1992). Meanwhile, he also incorporated bits of his failed first film into his screenplay for True Romance. Then he parlayed those early successes into Pulp Fiction. So it took him seven years from that first failure to upending the film industry.

And what did I do in the seven years following my failed novel? I bounced around a series of retail jobs before deciding to go back to school and change my major. I finally graduated in 1997, then I took a job as a staff writer at a local newspaper, which turned out to be a pretty poor career decision. I didn't write another word creatively in all that time.

Just hang in there, baby. You're doing great.

What sets Tarantino apart from less successful writers isn't his natural talent or his encyclopedic knowledge of movies. Those things can be developed. What he has that many lack is a persistence and drive to push through the low points of a career — the inevitable rejections, the technical limitations, the lack of money, the intimidating blank pages of a new idea.

Failure is never failure if we learn from it and do better the next time. Rejection is an opportunity to reflect and recalibrate if necessary.

The nature of writing screenplays or books is to dedicate months or years of hard work toward an idea that has little chance of success. You need to love the process and you need to be willing to see it through all its stages — from concept and development of the story to writing and editing and getting and incorporating feedback, then pitching and advocating in the hopes that someone with more power than you will take it on, then watching your baby get torn apart and deformed as more and more people get involved. And if you've done all you can do and even more with no luck headed your way, you need to continue on with new projects, taking all that you've learned and applying it to the next thing.

I saw a headline the other day that said the average screenwriter writes eight screenplays before making their first sale. I would argue that the average screenwriter writes one or two before giving up. But the payoff if you work as hard and as long as someone like Tarantino?

Mmm-mmmm. That is a tasty burger.

Double Feature Suggestions

- Pick any other Tarantino movie. Jackie Brown has always been my favorite. I've been lukewarm to most of his post-Kill Bill work, except I think Once Upon A Time in Hollywood is fantastic, right up there with his best. But really, you could go to school on anything he's done.

Screenplay Link

Now Yolanda, we're not gonna do anything stupid, are we?

Comments

Join to Comment

or

<< Before Sunrise << >> Write with me >>

I'm trying real hard to be the shepherd.

My Books

Recent Posts

- Before Sunrise

- Pulp Fiction

- Moonrise Kingdom

- Party Down

- Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

- The Limey

- La La Land

- The Apartment

- Kiss Kiss Bang Bang

- John Wick

- Election

- Casablanca

Story Circle Notebooks

|

|

These notebooks contain story circle templates and blank dot-grid pages that are great for breaking down your own creations or analyzing the structure of existing films and stories. Purchase from Amazon:

Help Me Choose

What movie should I write about next? I have a few ideas, but I‘m open to suggestions:

CatsChildren Of Men

Donnie Darko

Four Weddings and a Funeral

Good Will Hunting

Grosse Point Blank

Hell or High Water

Jo Jo Rabbit

La Dolce Vita

La Notte

Logan

Miller's Crossing

Moonlight (2016)

Never Let Me Go

Pan's Labyrinth

Punch Drunk Love

Rambo

Star Wars

The Big Lebowski

The Nice Guys

The Raid 2

or something else

Vote Results for Upcoming Posts

Thank you for your suggestion! Be sure to sign up below to be notified when new story circles are posted to the site!

Pan's Labyrinth (14%)

Donnie Darko (12%)

Star Wars (11%)

Jo Jo Rabbit (8%)

The Big Lebowski (7%)

Punch Drunk Love (7%)

Children Of Men (6%)

Good Will Hunting (5%)

Hell or High Water (5%)

Other

Thanks again! And hey, if you’d like to write one of these articles, hit me up.

Write for Story24

If you’re interested in contributing to this site, I would love to hear from you. Learn more here:

Other Business

Some of the links on this site are affiliate links. I earn a small commission when purchases are made after these links are clicked.

No comments yet.